The Moss

Fenn's, Whixall and Bettisfield Mosses used to be commercial peat cutting hubs. Now, the land is being slowly restored to precious peat bog.

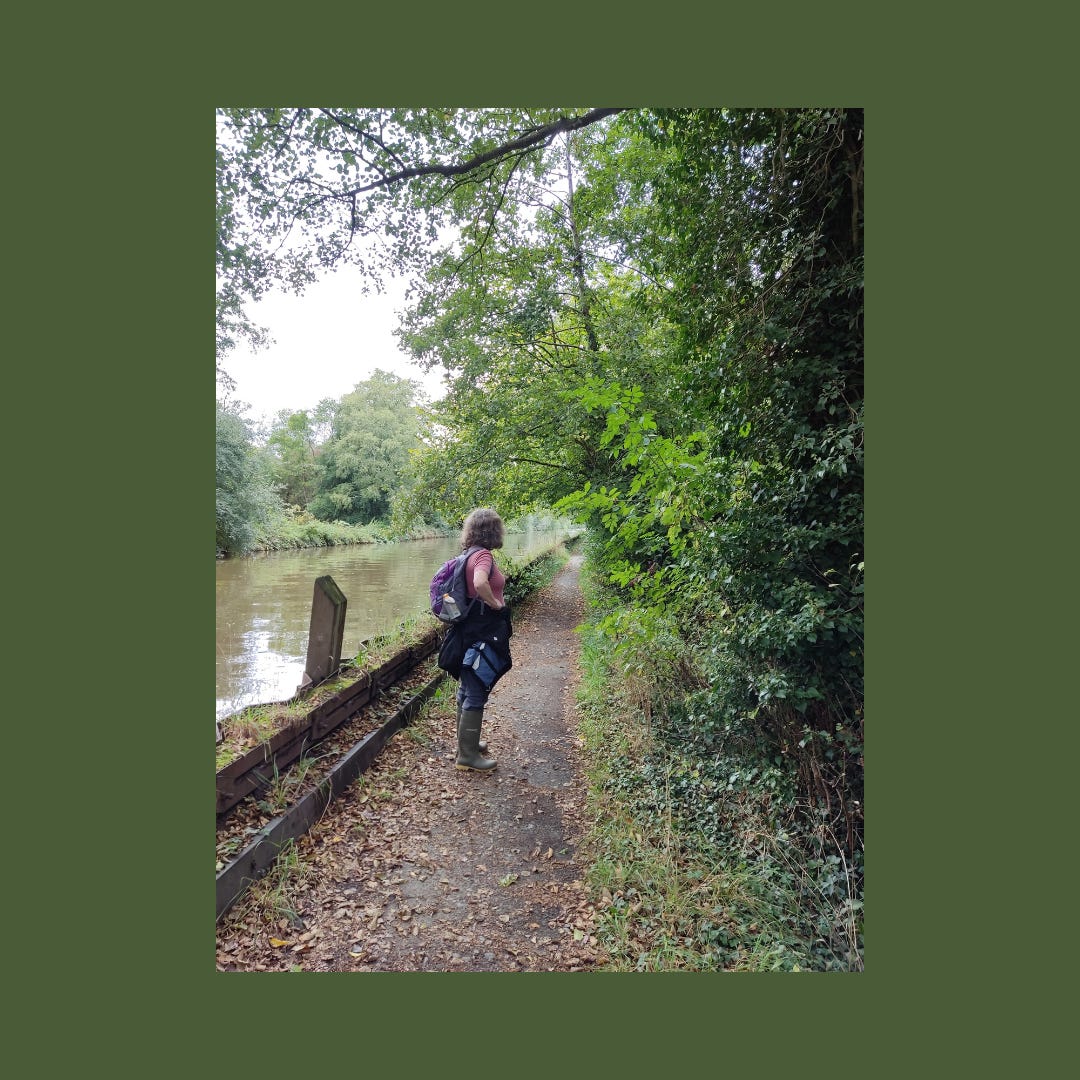

It is a damp day in early September. My mother is leading me down a canal path, where the boughs of the trees and bushes alongside are already beginning to turn to autumn - deep purple sloes with their milky haze, bright red rowan berries, wild rose hips and haws, blackberries and elderberries hanging heavy in the hedgerows.

The canal is quiet — there are a few fishermen, and we pass a man reading in a camp chair on the path, sweet woodsmoke rising from the chimney on his barge. We turn off the canal path and follow the track through a birch wood - the trees are dripping with recent rain, the ferns and brambles below blending into layers of darkening green. The birch trees would have been the first to come back to this land, my mother tells me, when peat cutting operations ended in the 90s. They are a frontier species, able to set seed in the most unwelcoming of habitats, providing shade and shelter for other saplings and dropping leaf litter to make the acidic peat soil more nutritious. But despite their carbon capture credentials, more trees are the last thing that this unique habitat needs.

At the edge of the Moss, there is a large raised viewing platform. We climb the wooden steps and look out over the strange landscape. It stretches flat for miles, eventually meeting a distant line of trees, unbroken except for scattered birch saplings. It is a savannah, a desert, a tawny empty space, holding only the sky which hangs grey and heavy above us. There is none of the bounty of the hedgerows, only patches of green and brown and scrubby purple heather. But despite appearances, this place is slowly being transformed back into a rich habitat, after centuries of human interference and extraction.

Commercial cutting began here in 1851, but local people must have been cutting the dark, dense peat as a source of fuel long before. Starting with horse-drawn wagons, production swiftly moved to steam powered combustion engines and eventually tractors. In 150 years, the level of the Moss dropped by 10 meters. Production was halted in the 1990s when the lease to the land was purchased by the Nature Conservancy Council, and the land is now managed by Natural England and Natural Resources Wales (the site straddles the border).

From our position on the viewing platform, my mother reads the landscape like a text. The birch saplings, heather cover and purple moor grass indicate soil that is dry and nutritious — in any other landscape a positive sign, but not according to the topsy-turvy logic of the bog. What makes peat bogs so unique is their nutrient-poor, acidic conditions, which allows moisture-storing sphagnum moss to thrive, creating conditions for other rare fauna and flora like cranberry, sundew and adders. My mother points to a patch of heather near the edge of the moss — it’s there because the area has been artificially dried out, using drainage channels that crisscross the landscape. She suggests that this area could have been where the cut peat was piled and stored before being transported to garden centres and horticultural wholesalers, eventually finding itself in rose beds and allotments across the country.

A little beyond, there is a swathe of purple moor grass, which has been able to establish itself in the abnormally nutritious soil, shading out the sphagnum moss and drying out the peat as it grows. The nutrients in the soil have probably come from nitrates in the atmosphere — this is a predominantly agricultural area, so the most likely sources are fertilisers and several large chicken farms nearby. My mother points out several pools ringed with a bright, unnatural green. Ideally the water would be fairly evenly distributed across the moss, so their presence could indicate blocked drainage channels. These pools often attract birds, and although the Moss provides a habitat for many bird species (such as the curlew, once a common farmland bird whose nesting patterns have been disrupted due changes in farming over the past 50 years), their concentrated presence also introduces further unwanted nutrients in the form of droppings. Whilst the Moss has finally been granted a protected status and commercial peat cutting has ceased, it’s clear that there is still a lot to be done to bring this disrupted ecosystem back into balance.

Back on the soggy earth, we get as close as we can to a damp patch of the bog without falling in. At first all is a yellowy-green, with dark patches and dips filled with water reflecting back the darkening sky. But, crouching down to look closer, there are mountains and valleys and lakes in miniature, trailing forests of cranberry and and open mouths of carnivorous sundews. My mother hands me a clump of sphagnum moss and tells me to squeeze it. I do, and watch the milky water drip back into the earth. Sphagnum moss can hold up to eight times its own weight in water, and links together like a carpet to catch and hold rainwater, until it eventually breaks down into peat.

Although today the Moss is huge and empty and completely devoid of human life, people are central to the Moss’s history. Between 1867 and 1889, three bog bodies were found in the Moss, two from the Iron Age and one from the Bronze Age. Perfectly preserved by the acidity of the peat, their skin was still intact, although tanned dark and leathery by millennia in the bog. They were reburied in local churchyards, which is a strange ending for those who, in the case of the Bronze Age body, would have had absolutely no concept of Christ, or in the case of the Iron Age bodies, are very unlikely to. In the fertile, nutrient rich soil of the churchyard, their bodies would have completely decomposed. Historical records show human activity on the Moss from the 1500s onwards, peat cutting rights and fines and regulations written into local law. In the great expanse of peat bog time, the 500 years of regulated human activity on it has been but a blip, but the damage we have caused has been great. As we squelch along the wet path, my mother points out the ways those who manage the land are seeking to undo centuries of cutting and drying and parceling up.

to be continued next time!